The information sector

At the root of so many problems is in the modern world is the fact that people are largely wasting their productive lives doing tasks abstracted from reality, involving no bodily movement and creating no physical product. In many cases, the employee even asserts when polled that their job is lacking any meaning. Physically productive jobs don’t pay. Instead, rewards are disproportionately distributed to speculative and rent-seeking industries. Most people have lost their professional dignity.

Abstract Jobs in the ‘Information Sector’

The economy has become more abstract as it becomes exponentially more complex, and Job roles are becoming exponentially more specialized. I mean exponential growth literally, as this is a situation in which a growing number of jobs grows an exponential number of interconnections and interactions, home for more jobs. But tied to complexity and less remarked-upon is the growing abstractness of our jobs. People are now working in what is best termed ’the information sector'.

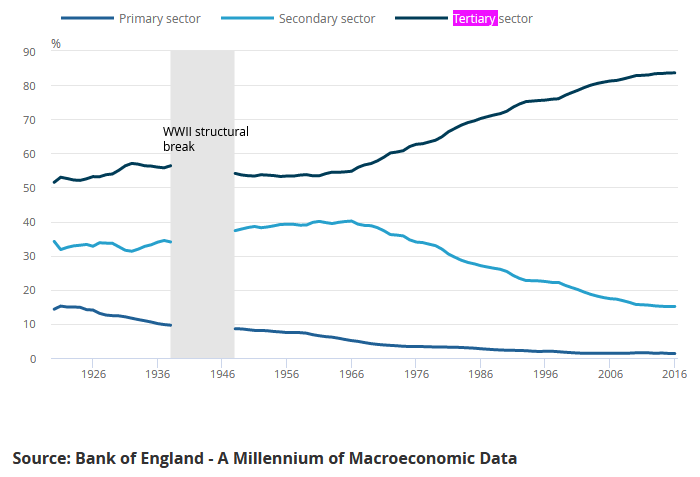

The US economy, like all other OECD nations, largely employ’s people in the ‘service’ sector. Using the typical three sector model, the break-down is: agriculture: 1.5%, Industry (mining, manufacturing, construction): 13%, Service: 80% and, Self-Employed: 5.5%. As of 2016, in the UK, the tertiary (service) sector employs 83.6% of people.

Taking the UK economy as an example, it can be seen that the share of jobs in the service sector rose from 55% in 1966, to 83% in 2010, after which it has plateaued.

But the three-sector model was developed in the 1930s and 40s, when the proportions were far more even and the nature of work was different. And the growth of the service sector has clearly not been in the provision of real services, rather in abstract services. This extended service sector or has typically been described as the finance, insurance and real-estate sector (FIRE). Alternatively, the Wikipedia definition of a wider ‘quaternary sector’ is a vague one.

Under the current three sector model and these additional categories, workers are classified simply because of the sector of the company paying them, not the activity they are performing. The official figures suggest that 7.9% of the workforce engaged in manufacturing in the USA, 13% including mining and construction, but even in those physically productive industries, less than half are working in non-information roles in the real world. From 27:30: in Larry Summers: The High Price of Getting it Right, Honestly with Bari Weiss from 18th August 2022.

Already in the United States, only about 4% of our workforce is involved in production work in manufacturing. You often hear the number “10% of the people are in the manufacturing sector”, but the majority of workers in manufacturing are accountants or personal assistants or marketing people or people who are doing something other than producing.

― Larry Summers: The High Price of Getting it Right, Honestly with Bari Weiss from 18th August 2022.

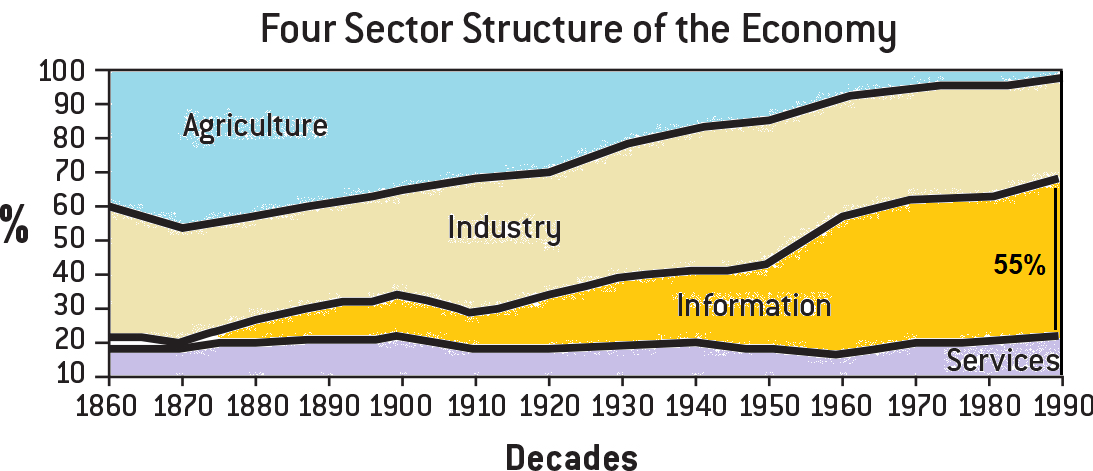

But I think there is a better definition: ’the information sector’, one that represents a more relevant categorization for the modern world. In 1977 Marc Porat published ‘The Information Economy: Definition and measurement’ (free download) where he proposed a more useful, but not widely adopted framing which classifies all jobs as ‘The Information Sector’ or non-information sector. This model is takes into account the work they are performing rather than the sector of their employer. Already, in 1977, according to his definition, 50% of the workforce participated in the information sector (page 120).

We are talking about administrators, consultants, clerical and accounting staff, IT professionals. This is the segment of the economy that has grown. In my experience, a large proportional of this time is, people editing information as these move it between different Microsoft Office document formats and discussing it at length in meetings. Note, the ‘information sector’ is not to be confused with the ‘information industry’ or the ‘IT sector’.

In 1992, a UCLA information scientist, Robert M. Hayes, presented an updated version of Mark Porat’s model at the New Information Technology Conference. He estimated that the information sector had risen to employ 55% of the total workforce of the USA by 1990. He clarifies that almost exactly half of this workforce is from Information sector companies, and half are employees from other sectors, whose activity is ‘information-oriented’. In Bullshit jobs, Graeber has cleaned-up and digitalized the 1992 graphics. But it is still terrible, so I have jankily coloured it in as below to show unambiguously that it is a stacked line graph:

I am yet to find a 2022 version of this graph, and I don’t think data is available. David Graeber notes in Bullshit Jobs “no one, to my knowledge, has pursued this particular breakdown through to the present”.

But, to get a lower bound estimate of information sector jobs, assuming the same proportion of other sector workers are involved in information activities agriculture: 33%, industry: 44% and, services: 69%, as Hayes assumes in 1992, by reading the ratios from his graphs we would have an information sector employing of 64% of Americans. I would guess this to be even significantly more than this, as administration roles across all industry sectors are well-known to have ballooned even since 1990.

| Sector | Proportion (2022) | Proportion of Sector Actually doing Information Activities(1992) | 2022 Information Workers Proportion (col 1 x col 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 1.5% | 33% | 0.5% |

| Industry (mining, manufacturing, construction) | 13% | 44% | 6% |

| Service | 80% | 69% | 55% |

| Self-Employed | 5.5% | assume 50% | 3% |

| Total | 100% | n/a | 64% |

In conclusion, the vast majority of people in the USA are doing entirely abstract jobs, totally disconnected from the real world.

Bullshit Jobs

In addition to their abstractness, a large minority of people across the western world believe their jobs are totally meaningless.

In the UK, the question was ‘Is your job making a meaningful contribution to the world’ ― YouGov, 2015 Is not’: 37% with ‘Is’: at 50% and ‘Don’t know’: 13%

In the US, the question was, ‘Do you think that your job is or is not making a meaningful contribution to the world?’ ― YouGov, 2015 ‘Is not’: 24%, with ‘Is’: 63%.

In the Netherlands, the question was the URL for the original poll broken (“Vier op tien werknemers noemt werk zinloos , accessed July 10, 2017"), but it is referenced in this 2018 article which I have extracted from the HTML and translated in this PDF. It was apparently conducted by Schouten & Nelissen on 1,900 Dutch people after 2015 and claims the 40% of respondents replied that their job is meaningless. Although, I’m unclear on the original question and response options.

― Schouten & Nelissen, 2015

All polls are difficult but this one particularly so because it is very sensitive to the exact phrasing of the question, should it focus on ‘meaning’, ‘value’, ‘utility’, ‘importance’. All of these are sensitive to the individual’s prejudices and self-image, and a comprehensive definition is not provided. Secondly, this question is an existential one as work gives structure and meaning to one’s life. It is not trivial to attest that your life’s work was wasted. Individuals are best placed to understand the value of their own role, but they are perhaps the most likely to defend its importance, for the sake of their own ego and self-worth. But this means that then an individual claims his job is useless, we should believe him.

Speculative Jobs

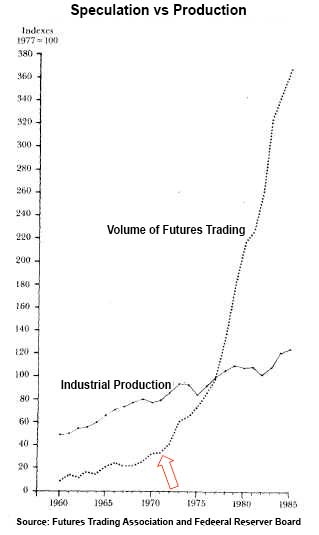

I have written separately about the growth of speculation as an excellent source of wealth capture which provides no productive output. Speculating on assets is a better investment of your time if you have better than average market information, or you have good risk management techniques.

From https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/

It just seemed to make sense that, just as Wall Street profits were derived less and less from firms involved in commerce or manufacturing, and more and more from debt, speculation, and the creation of complex financial instruments, so did an ever-increasing proportion of workers come to make their living from manipulating similar abstractions.

Suffice to say is clear to all of educated society knows this, especially Nancy Pelosi definitely knows this who has because amazing rich from her $200,000 a year salary. Michel Houellebecq had summed it up well in Plateforme in 2001:

‘Valerie’s father was forty-eight, his wife, forty-seven; they had dedicated the best years of their lives to a hopeless task. They lived in a country where, compared to speculative investment, investment in production brought little return; he understood that now’.

― Michel Houellebecq, Plateforme, 2001

Life is already unfair, but the certainty that your productive job, is worse paid than a trading job, is especially depressing.

Gloomy vs Glossy Jobs

As you progress through your working life, you become aware of a career hierarchy, if you were not already. You discover that society is not really divided into three classes. It is divided into the rich and the poor. And it’s not between the billionaires and everyone else. It is more between those with the elite jobs and everyone else. These elite jobs since, the 80s have been Investment Banking, Management Consulting, Corporate Law, Private Medicine and more recently Big-Tech.

Daniel Markovitz’s 2019 book ‘The Meritocracy Trap’ focuses on the top 1% and the top 4% that surrounds them and might one day be in the top 1%. Almost all the income growth in America has happened there in the last 30 years. The top 1 percent of households now captures about a fifth of total income.

In Chapter Six he talks about glossy and gloomy jobs and states:

The top jobs pay so well because a raft of new technologies has fundamentally transformed work to make exceptional skills enormously more productive than they were at mid-century and ordinary skills relatively less productive. … The more lyrically minded have said that the labour market is increasingly divided up into “lousy” jobs that require little training, involve simple work, and pay low wages, and “lovely” jobs that require elaborate educations and provide interesting and complex work at high pay. … This lyricism, however, ignores the most important harms that the transformation of the labour market imposes. It papers over the fact that the lousy jobs are not just boring and low-paid but also—indeed, specifically on account of job polarization—carry low status and afford no realistic prospects for advancement. … It is therefore more apt to say that the labour market has divided into gloomy and glossy jobs: gloomy because they offer neither immediate reward nor hope for promotion, and glossy because their outer shine masks inner distress.

— Daniel Markovitz, The Meritocracy Trap, 2019

The vast majority of people are working these gloomy jobs with:

- “little training, involve simple work, and pay low wages”

- “carry low status and afford no realistic prospects for advancement”

- “offer neither immediate reward nor hope for promotion”.

The Destruction of the Middle Class

The middle class has already been thoroughly destroyed in his Podcast with Sam Harris, #205—The Failure of Meritocracy May 23rd, 2020. For kids born in 1940, almost all became richer than their parents. Only the top 95% percentile were not certain to be richer than their parents.

Markovitz then summaries the class resentment that this produces:

All the elite jobs, law firms, investment banks, management jobs, specialist medical doctors require one to have gone through a version of this fancy education. Those institutions exclude middle and working class families by the number of hoops required to jump through. Unless you are incredibly exceptional, you will not have enough privilege to get along. Those that are excluded get appropriately angry and resentful and turn against the institutions, the professional companies, the forms of expertise, the schools that people on the outside correctly think are underwriting their disadvantage and exclusion. A populist like trump exploits that class resentment. Trump inherited a lot of money, but is not part of this system of training, education and professional certification that people correctly see as the principal source of their exclusion. Not his inheritance. All the doctors and lawyers and bankers and CEOs and elite managers, who are training their kids and getting them into the best schools and buying houses in the best neighbourhoods and getting them into the best colleges, is what keeps most Americans down.

— Sam Harris Making Sense Podcast #205—The Failure of Meritocracy, David Markovitz, May 23rd, 2020