British historical periods

History was always interesting, but somewhat impenetrable to me because the nomenclature of various periods was never explained. I had a chart on the wall of all the monarchs of England, but I never absorbed it in the way that I did maps, because there was no self-evident or logic to the naming, no context and thus, no stories evoked when I read words like Early-Modern, Plantagenet, Georgian and Hanoverian. Whereas, reading a word like China, Germany, and Brazil awoke something in my mind.

Knowledge is a tree in the human brain. If the trunk is never built, there is nothing for the branches and leaves to cling to, and they float away in a wind of meaningless boredom. In most peoples understanding of history, the trunk is rarely built in at all. Knowledge resources are mostly made by either experts, and or hired-hands. The experts are more interested in esoteric details than teaching basics and the hired-hands don’t understand or care about the subject and simply regurgitate the existing material. Both add needless complexity. The worst and most common example is the lack of any plain English explanation for basic naming conventions.

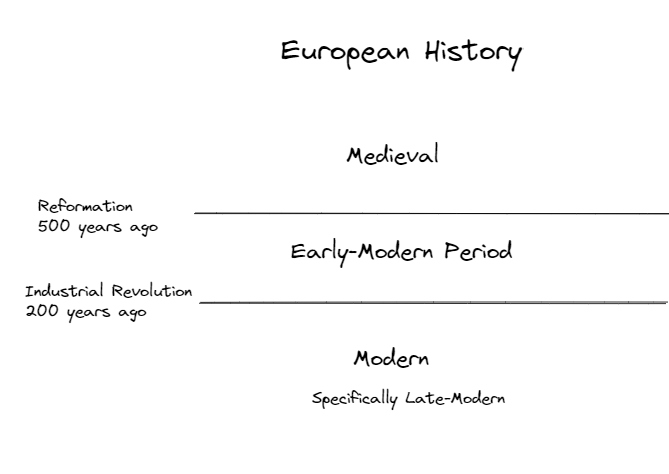

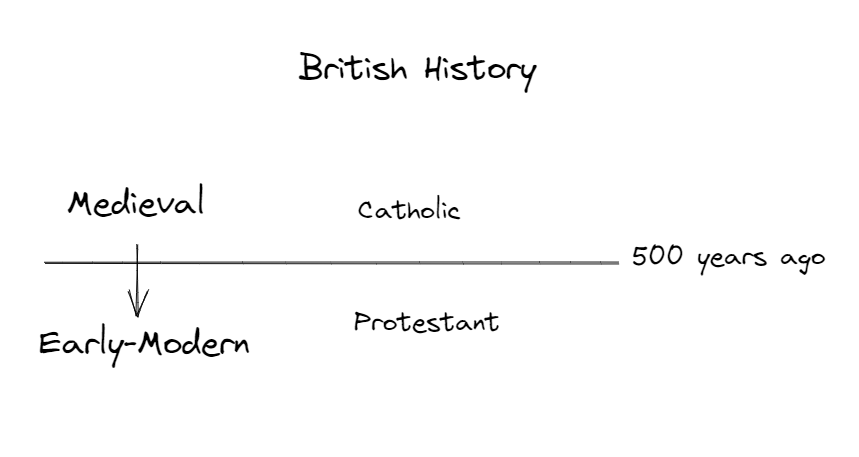

For example; the era of the last 500 years are collectively called the early-modern period.

‘Early-modern’ is the sterile, placeholder that we have defaulted to using. Modern originates from 500 years ago, when people first started to think of the world as progressing rather than cyclical. They started to use the word modern ‘present’ to describe themselves, at the apex of that progression. It began with the renaissance and then continued with the enlightenment. Now ‘modern’ is the technical word for that whole that period, even though it is contradictory to conventionally understood English to refer to something 500 years ago as ‘modern’.

This is rarely explained despite being the defining feature of the entire enterprise of the study of ‘modern’ history. It seems like the most basic of knowledge, yet in every domain I learn about, I realize there is a wink-wink nudge-nudge inner-circle type knowledge of trivial but foundational things that you only learn through experience, but that people never write down. Is it because people are not actually concerned about teaching, rather about showing that they know important seeming things in order to achieve status? It makes sense, if you are a professional concerned with furthering your reputation, why lower yourself to trivialities? What are people going to do; hold you to account for failing to deliver learning outcomes? You’re a professor, an academic, or an author; not a teacher.

The second convention is that the eras within the early-modern period in British history are mostly referred to by some logically inconsistent version of the King’s name, especially when there were several successive kings with the same name. But the application of this is totally random. For example, to refer to a period where a Charles is the king, apparently we can’t say Charles’s era. We use the Latin version Carolinus. And three forms of this are used depending on which Charles you are talking about: ‘Carolingian’ for Charles Martel of the Franks, ‘Caroline’ for Charles I of England and Carolean for Charles II of England.

Kings with short rules get one:

- King Edward VII who reigned for 9 years in the Edwardian Era,

- King James I who reigned for 22 years in the Jacobean Era

And yet none of the long reigning King Henries got one:

- King Henry III, who reigned from 1216 until 1272, a period of 56 years, or

- Henry VI who ruled intermittently from 1422 to 1471 for 38 years or

- Henry VIII who ruled from 1509 to 1547 for 37 years.

Is this because we just decided that only in the early-modern period (after 1450-ish) we should start calling eras after individual Kings? Or is it just because Williamite refers to the allegiance to William III of Orange and his ‘Williamite War’ and also ‘Guillaume-ian’ (the Latin) sounds horrible? That didn’t stop them from using Jacobean to refer to the 23-year reign of James the First starting in 1603. And Jacobite to refer to the follow’s of James I’s grandson, James II once he was ’encouraged to vacate the throne’.

Anyway, starting with Queen Elizabeth, some of the periods are referred to by the Monarch’s name. Obviously this convention breaks-down when you get a repeated name or a name that doesn’t sound good. Here is the list of monarchs since the first monarchic-named era ‘Elizabethan’ era:

- Elizabeth = Elizabethan ✅

- James I = Jacobean ✅

- Charles I = Caroline ✅

- Oliver Cromwell ‘Lord Protector’

- Richard Cromwell ‘Lord Protector’

- Charles II= Carolean—rarely used ✅

- James II = Jacobite means a follower of him

- William II = Williamite means a follower of him

- Anne

- George I = All successive Georges collectively called the Georgian Period ✅

- George II = Ditto ✅

- George III = Ditto ✅

- George IV = Ditto ✅

- William IV

- Victoria = Victorian ✅

- Edward VII = Edwardian ✅

- George V

- Edward VIII

- George VI

- Elizabeth

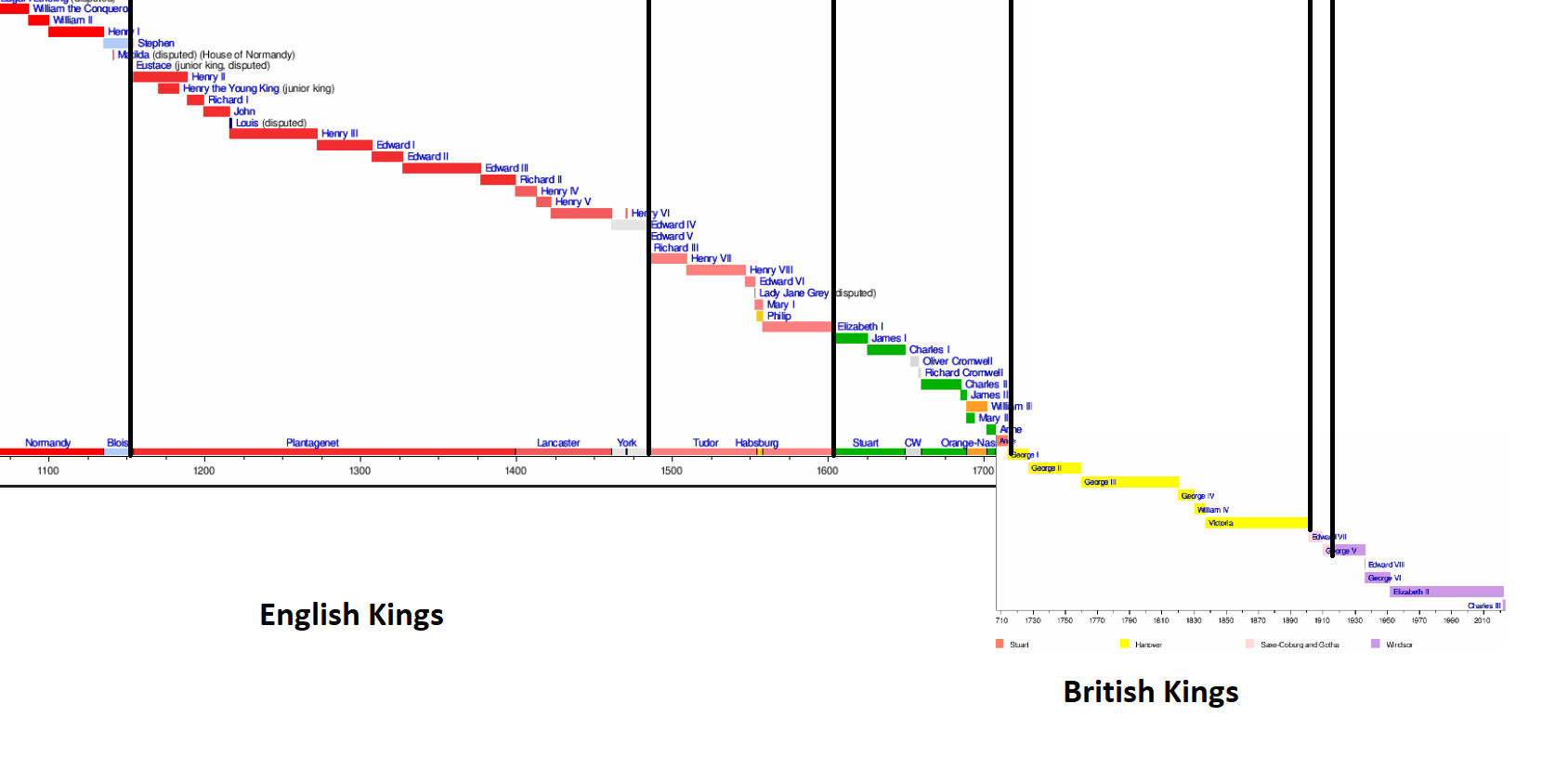

In contrast, in the Medieval period (pre-1450-ish) historians exclusively use the dynasty (Norman, Angevin, or Plantagenet), not the royal first names to refer to a particular era with one exception. ‘Edwardian’ occasionally means the period of Edward III’s rule in the Hundred years’ war. Also known as the Edwardian War.

Why do we draw the line at 1500?

A number of things changed around this time. The Portuguese founded the first European colonies in Ceuta, the reformation of the Catholic Church occurred and the ‘Renaissance’ began, triggering the use of the word ‘Modern’ to describe the sense of forward trajectory.

Perhaps most importantly, Protestantism spread following Martin Luther’s proclamation due to the Gutenberg printing press and Henry VIII of England used a desire for an independent protestant church as an excuse to leave the grip of the Papacy. It’s no coincidence that Britain, Scandinavia and Germany, the nations at the edges of the reach of the Pope’s power were those that protested. They were subject to corrupt and arbitrary rule, over which they had no ability to influence.

Medieval

Is there a time when Britain was ruled by ’local’ kings? The Anglo-Saxons who took control in the centuries following the Roman rule, known as the ‘Early-middle ages’ or ‘Dark-ages’ were from Angle-land and Saxony, around Hannover and Denmark. Hence, the term Anglo-Saxons. And England. But the History of the England is one ruled by dynasties from foreign lands. With no exceptions. England had no home-grown dynasties anywhere in its history. Obviously the definition of home-grown changes as invaders eventually become just as local as the locals after a few centuries but here is a comprehensive list:

- Anglo-Saxons — Modern Germany and Denmark

- The Danelaw — Danish

- Normans — France

- Blois — France

- Angevin Anjou — France

- Plantagenet Anjou—Originally French

- Tudor — Welsh

- Stuart — Scottish

- Orange-Nassau — Dutch

- Hannover — Germany

- Saxe-Coburg-Gotha — Victoria married into another German house

- Windor — George V changed the name in 1917 for obvious reasons