Hundred years war

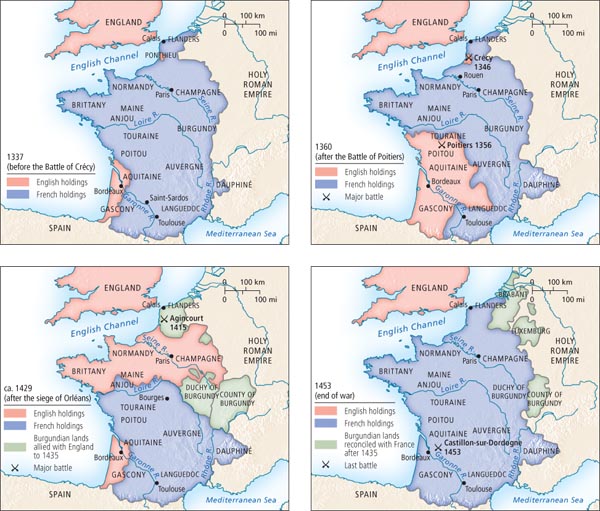

The Hundred Years War, is a fascinating and critical part of British and French history. The dispute originated directly from Edward III’s claim to the French crown through his mother, who was the sister of the previous French king. However, the roots of this protracted conflict can be traced to the broader socio-political ‘crisis of 14th-century Europe’. The war, characterized by intermittent periods of intense fighting and relative calm, ultimately spanned an astonishing 116 years.

To fully grasp the nature and implications of the war, it’s crucial to understand the contrasting structure of the English and French monarchies at that time.

England’s monarchy was highly centralized. The entire kingdom was considered crown-land, and the barons governed their territories at the king’s behest. The king, however, was answerable to a parliament that maintained checks on his power. This ancient system, whose origins can be traced back to Anglo-Saxon times, and was nearly extinguished by the Normans had been re-established through significant events in the 1200s like the signing of the Magna Carta and the Provisions of Oxford.

In contrast, the French monarchy operated differently. Until the late 15th century, only a fraction of France, primarily the region surrounding Paris, was designated as crown-land or the ‘Royal domain’. The remainder of France was composed of various Duchies and Counties, operating as semi-autonomous vassal states. The Dukes and Counts of these regions, while pledging ‘homage’ to the French king, retained significant independent powers, creating a governance structure akin to that of the Holy Roman Empire.

In the event of a Duchy’s ruling house becoming extinct, ownership typically defaulted to the French king, who would then usually grant the Duchy to a close relative or second son within a few years.

In France, the term ‘Dauphin’ referred to the heir apparent to the throne. As part of his preparation for future rulership, the Dauphin was granted the Dauphiné, a large region in southeast France, for his personal governance.

Thus, these differing systems of governance were key to the inception and progression of the Hundred Years War, setting the stage for a conflict that would shape the future of both nations.

Part I: Edwardian War

When Charles IV of France passed away without a male heir in 1328, the last in a series of four successive kings of the French Capet line to do so, a succession crisis was triggered. Edward III of England, then aged 16 and the closest male relative of Charles IV through his mother Isabella, was pushed forward as a claimant by his mother. However, this claim was promptly rejected by French jurists, who referred back to the Salic law. This law, dating back to the reign of King Clovis around 500AD, stipulated that the French crown could not be inherited through a female line. Consequently, the throne went to Philip VI, the first cousin of Charles IV.

Edward III initially paid homage to Philip VI, accepting him as the rightful king of France for the first nine years of his reign. But in 1337, Edward decided to stop paying homage, largely because of Philip’s interference in Gascony, a core province of the duchy of Aquitaine. Edward III was the Duke of Aquitaine, and the Gascons preferred to govern themselves rather than being subject to external interference. In retaliation, Philip VI seized Edward’s lands and the Duchy of Aquitaine. This prompted Edward to claim the French crown himself, an assertion that was once again rejected by the French. War broke out, marking the start of the Hundred Years War.

In this early phase of the war, there were several significant battles and campaigns, which included the naval Battle of Sluys (1340) and the terrestrial Battle of Crécy (1346). These conflicts saw the English forces, with the advantage of their longbowmen, inflict devastating defeats on the French.

In 1348, Europe was hit by the Black Death, a pandemic that led to a significant decrease in the population. The effects of the plague played a role in halting the conflict temporarily, as it ravaged both England and France. The war resumed in earnest by the 1350s.

In 1356, Edward’s son, Edward, the Black Prince, defeated and captured John II of France at the Battle of Poitiers. John II’s capture led to a shift in the dynamics of power in the French court, leading to a period of instability and infighting among the French nobility.

The first phase of the war concluded with the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. In the treaty, Edward III renounced his claim to the French throne in exchange for full sovereignty (as opposed to vassalage to the French crown) over the expanded English territories in Aquitaine. However, the peace was short-lived, as disputes over the treaty’s terms and the French king’s ransom led to the resumption of the war in 1369, still under Edward III.

Part II: Caroline War

This second phase of the Hundred Years’ War is often called the “Caroline War.” It saw the French, under King Charles V and his capable constable Bertrand du Guesclin, successfully recapture much of the lost territory through careful strategy and guerrilla warfare. Edward III, died in 1377 leaving the crown to his son, Richard II of England as the Black Prince, had already died of dysentery. This phase of the war ended in 1389 with the signing of the Truce of Leulinghem by Richard II.

Part III: Lancastrian War

The last segment, known as the Lancastrian war, was initiated by Henry V ‘of Monmouth’ in 1415. Henry said that he would give up his claim to the French throne if the French would:

- pay the 1.6 million crowns outstanding from the ransom of John II (who had been captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356), and;

- concede English ownership of the lands of Normandy, Touraine, Anjou, Brittany and Flanders, as well as Aquitaine.

- Henry would marry Princess Catherine, the young daughter of Charles VI, and receive a dowry of 2 million crowns.

The French responded with what they considered the generous terms of marriage:

- No payment for ransom

- an enlarged Aquitaine

- with Princess Catherine, a dowry of 600,000 crowns, and

Henry persuaded the English parliament to resume the war with France.

The key rival forces at the start of the Lancastrian were the Duke of Burgundy and the Duke of Orleans.

Until 1361, Burgundy was administered by the ‘Burgundy’ Cadet branch of the Capet house. The rulers of both became when Philip I died with no heirs. King John II of France therefore inherited the Duchy, and 2 years later, granted it to his youngest son, Philip II the Bold, who formed a new cadet Branch of Valois also called ‘Burgundy’. The Duke of Burgundy was the undisputed premier peer of the King of France at the time.

Meanwhile, the County of Orléans had been part of the royal domain since around 950. It became a convention to gift the title of ‘Duke of Orleans’ to the king’s younger son, despite it being a county rather than a Duchy. At the time of the Lancastrian war, it was gifted to Louis I, the second son of Charles V. The Duke of Orleans and the Duke of Burgundy became bitter rivals in the succeeding decades.

In 1393, King Charles VI went mad and Phillip the Bold, Charles’ uncle, initially became the regent, resuming the role he had played during the King’s childhood from 1380 until 1388. But power gradually swayed to the king’s Brother, Louis I, Duke of Orleans.

French Civil War

Philip the Bold died. So when John I, the Fearless of Burgundy, became Duke in 1404, he immediately entered a power struggle with the king’s brother, Louis I, Duke of Orleans for control of the regency. He did not deny assassinating Louis I in the streets of Paris in 1407. Louis’s son, Charles the new Duke of Orleans, immediately initiated a war against John the Fearless with support from his father-in-law; Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac. This was known as the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War. The King of France was not initially involved. It was a war between two duchies.

Both sides tried to seize control of the Dauphin, Louis of Guyenne who was 10-years-old at the time. His brother, Charles, who would eventually become King, was only 4.

Charles VI, due to his mental illness, didn’t actively “take a side” in the conflict. His inability to rule effectively caused a power vacuum that was filled by these feuding factions. His wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, tended to align more with the Duke of Burgundy, particularly after the assassination of Louis I, Duke of Orleans (Charles’s brother) by John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that Charles himself took that side.

At different times during the civil war, both the Armagnacs and the Burgundians took control of Paris and the surrounding crown lands, effectively commandeering the army in these areas for their own use. During this time, many of the soldiers would have been mercenaries, who were loyal primarily to whoever was paying them, rather than to the king or any particular noble. Therefore, the alignment of the army from the crown lands could have shifted multiple times during the course of the civil war, depending on the current balance of power.

English Invasion

Henry V of England, aged 29, invaded Harfleur, Normandy in August 1415, where he challenged the Dauphin, Louis, to on-on-one combat to decide the outcome. The Dauphin, 18, did not accept. This is the Dauphin character from Shakespeare’s play ‘Henry V’. He was called Louis, Duke of Guyenne. After capturing Harfleur, Henry embarked on a raid eastwards across the northern coast. He planned to return to England from by Calais.

During the English invasion, the Burgundians remained neutral, but the Armagnacs assembled a sizeable army which blocked Henry V at Agincourt on his road to Calais in October 1415. Henry crushed this army at the battle of Agincourt. Burgundy sent no troops to the battle, although two of John the Fearless’s brothers independently elected to join and ultimately died in the battle. The Dauphin, Louis, was not actually present at the battle of Agincourt. He was probably ill with dysentery at the time and he died within two months, leaving his brother, Charles who the heir to the French throne the new Dauphin for the remainder of the war and who would eventually become Charles VI.

By 1418, Burgundy was still neutral against England and, John the Fearless of Burgundy, acting in his own interests to secure the regency of France over the King’s brother, occupied Paris, holding the mad King captive, but the new Dauphin, Charles, aged 15, escaped. With this new power and territory, John was thus in favour of meeting the new Dauphin, Charles, in order to sign up to an advantageous peace. A meeting was organized in 1419, in which he was assassinated by the Armagnacs.

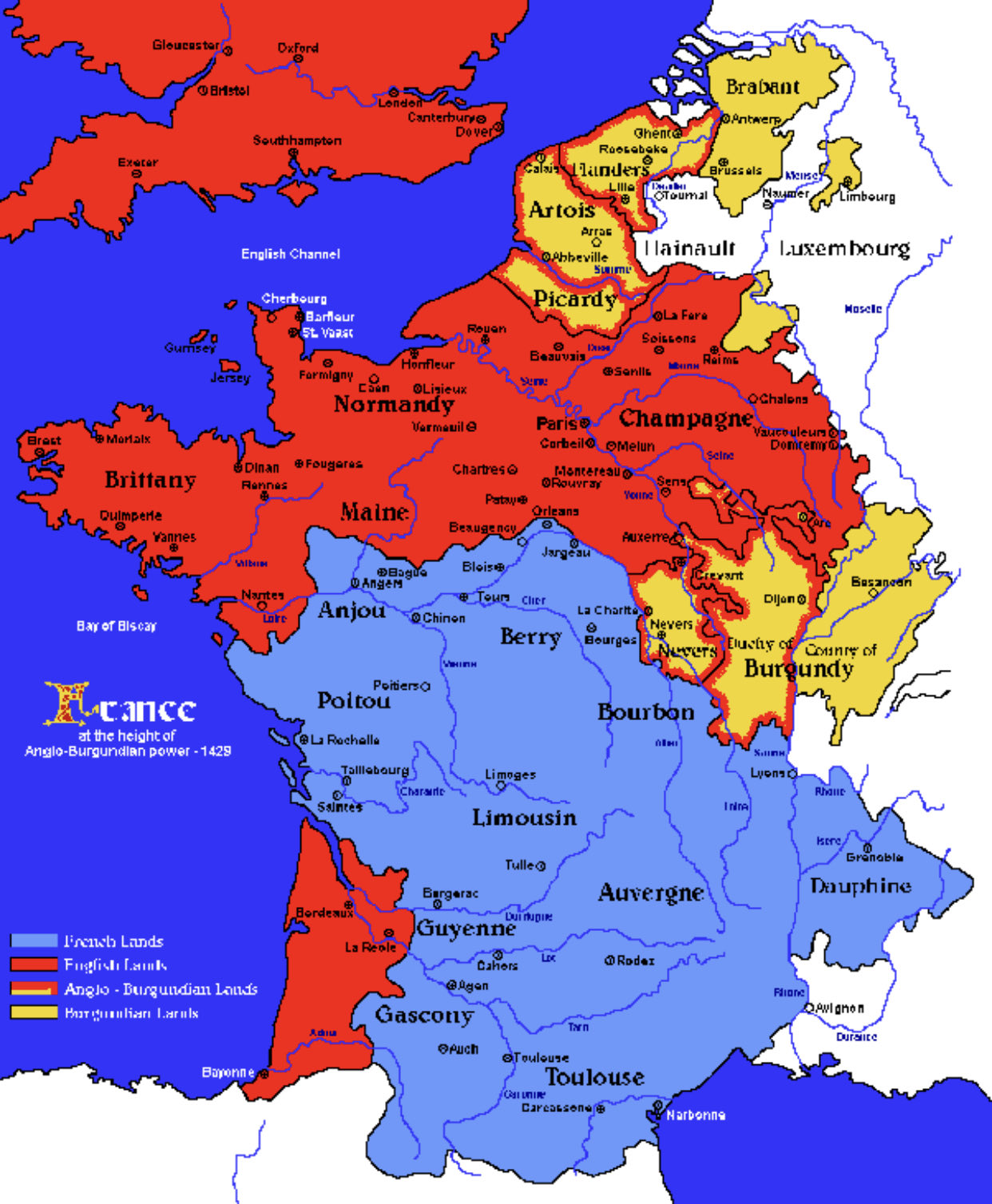

Anglo-Burgundian Alliance

Philip the Good, aged 23, the new Duke of Burgundy, then entered into a formal alliance with the English, who by 1420 had taken the entire north coast of France. The English and Burgundians each signed the treaty of Troyes of 1420 in which the mad Charles VI, captive in Paris, was coerced into legitimating Henry V as the successor to the French throne and delegitimizing his own son; Charles, the Dauphin who would become Charles VII. It also arranged the marriage of Henry V to Charles the Mad’s daughter, Catherine of Valois which legitimated any male heirs which Catherine produced.

This confluence of interests was known as the Anglo-Burgundian faction, supporters of Henry V. The French rump-state was known as the ‘Armagnac’ or ‘Royalist’ faction, supporters of the dauphin, Charles VII.

The following is England at the height of it’s power in the hundred years war in 1329.

Death of Henry V

Henry’s wife Catherine produced a son, Henry VI in 1421. But Henry V died of dysentery within 18 months, followed 2 months later by Charles the mad. Henry VI, who was 11 months old at the time, inherited the throne of France. The crown lands of France were thus directly governed by the King of England.

Unsurprisingly, Charles the Dauphin, future Charles VII refused to accept the inheritance of Henry VI and continued the war. A French rump state continued to fight as before.

Until 1428, the English, led by Philip of Burgundy and the Duke of Bedford saw yet more success.

Joan of Arc

It was in 1428 that Joan of Arc appeared and the Armagnac fortunes improved. She re-invigorated the defence of Orleans in 1429, eventually breaking the siege with a new offensive. She convinced the Dauphin to crown himself in Rheims, marching north through enemy territory in the process. Henry VI was later coronated as King of France in Paris at age 10 in 1431 in response. Joan was eventually captured, and was burned at the stake a year later in 1431.

English Defeat

The English continued to suffer defeats until 1435. Their failure was cemented when the Burgundians their essential ally, still led by Philip the good, switched sides. Paris was recaptured by Charles VII the next year. The hostilities continued until the English lost control of Bordeaux in 1453, leaving only the Pale of Calais. It ended without a peace treaty. The English eventually lost Calais in 1558.

The English royalty retained their claim to the Kingdom France, until King George III used the Act of union with Ireland to drop it in 1800. The fleur-de-lis was removed from the British coat of arms, over 400 years after Edward III had added it.